The great musician Lauren Hill once said, “Fantasy is what people want but reality is what they need.”

The great musician Lauren Hill once said, “Fantasy is what people want but reality is what they need.”

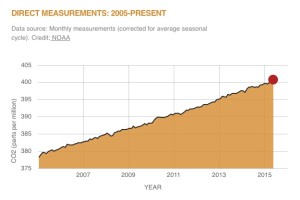

And the reality is that the climate movement is failing. See this graph? That’s a measure of carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere from 2005 to mid-2015. The trend is up. That means we’re losing. Until that trend is heading steeply in the other direction, we’re in trouble.

There are some encouraging signs. For the first time, carbon emissions flatlined through 2014, not increasing above the 2013 levels. But what most people don’t appreciate is that this change is a reduction in the acceleration of carbon emissions. The year 2014 simply avoided surpassing 2013 to become the worst year for carbon emissions on record. Instead, it was a tie.

This does not represent a victory. It represents a slowdown in the acceleration of how badly we’re getting our asses kicked. To win, the level of annual carbon emissions must plummet — on the order of 80-90% in the next 20-30 years, according to the climate scientists we have spoken with.

#ShellNO and Other Campaigns Against Fossil Fuels

In Seattle, the #ShellNo campaign to stop the Arctic oil drilling rig Polar Pioneer has thus far been unsuccessful. Despite the huge popular opposition, despite hundreds of kayaktivists taking to the water to block the rig, despite support from groups as disparate as the Seattle City Council and Greenpeace, the rig was not stopped.

In Seattle, the #ShellNo campaign to stop the Arctic oil drilling rig Polar Pioneer has thus far been unsuccessful. Despite the huge popular opposition, despite hundreds of kayaktivists taking to the water to block the rig, despite support from groups as disparate as the Seattle City Council and Greenpeace, the rig was not stopped.

And remember: this is only one small fraction of the expansion of fossil fuels; even if Arctic drilling is ultimately stopped, that does not address the already-established impacts.

So why aren’t we able to win?

“Corporations and their owners have learned quite well that when you control the law, you can rise swiftly to power and wealth by shredding bothersome laws adopted by communities,” writes Thomas Linzey, a lawyer and activist with the Community Legal Environmental Defense Fund (CELDF).

Fundamentally, according to Linzey, the problem is that the law is on the side of those in power. Destroying the planet is legal. Propping up a racist police force is legal. The CELDF analysis begins with the constitution, which they recognize as a document that was written by the rich to protect themselves and their power from the rest of the people.

Linzey and his team at CELDF work with communities around the United States (and the world) to implement a revolutionary form of local lawmaking. At its basis, it challenges the argument that federal and state laws that permit destructive projects (like oil & gas drilling, factory farming, mining, etc.) trump any local opposition to the project.

Linzey and his team at CELDF work with communities around the United States (and the world) to implement a revolutionary form of local lawmaking. At its basis, it challenges the argument that federal and state laws that permit destructive projects (like oil & gas drilling, factory farming, mining, etc.) trump any local opposition to the project.

It works like this. First, local organizers from a region under threat must contact CELDF. After learning about the issue, CELDF (which is funded by grants and doesn’t charge for it’s services) sends a trainer to the community to hold what they call a “Democracy School,” a two-day training that explains the legal roots of corporate power.

This is where their strategy goes off the rails. CELDF says the regulatory system isn’t broken; it’s doing exactly what it is meant to do, which is to direct people’s anger and frustration into a mess of bureaucracy that ultimately leads nowhere. The system has no teeth. So instead of this traditional approach, CELDF helps local organizers draft a local law that not only prohibits the project they’re trying to stop, it also removes rights from corporations within that jurisdiction and gives legal recognition to the rights of nature.

In their model, a river — through a human proxy — could sue a company that was causing it harm and argue that the rights of river to exist in a natural state were being infringed upon. This has actually happened. In 2008, CELDF helped the nation of Ecuador include rights of nature in their constitution, and the law has been used there to prevent “development.” In one case, local people brought a lawsuit against an oil project on behalf of a local river, and they won.

In the US, this model is blatantly illegal, since it goes against the constitution, which was set up to protect the rights of businesses. But that is the whole point, says Linzey. “We call it municipal civil disobedience.” And at its core, it’s a grassroots strategy to move from community to community, agitating for people to reclaim their rights to self determination in a grassroots effort to take back the government. The aim is to start with towns and move to counties, states, and eventually to the federal government, forcing meaningful changes into the very structure of law.

It’s not a simple model to implement. It’s only possible in certain communities, since the legal circumstances can vary from town to town and state to state. Getting a measure on the ballot can be difficult, and then there has to be enough engaged citizen power to actually pass the measure into law. It’s a very tricky proposition, as some communities (like Spokane or Bellingham, both towns in Washington State which have been trying to implement a CELDF-style law for several years without success) have learned.

The CELDF model requires dedicated organizers, citizen buy-in, an engaged public, and time. But when these resources can be mobilized, the changes can be profound.

MEND

The second model is equally revolutionary. It comes from the Niger river delta, a vast network of swamps and wetlands that stretches for 27,000 square miles. This is the largest wetland in Africa, and is home to extensive biodiversity.

The second model is equally revolutionary. It comes from the Niger river delta, a vast network of swamps and wetlands that stretches for 27,000 square miles. This is the largest wetland in Africa, and is home to extensive biodiversity.

In 1956, British colonial forces discovered oil, and ever since, oil companies — especially Royal Dutch Shell — have propped up a series of authoritarian governments that are willing to facilitate oil extraction. With more than 2 million barrels per day extracted, the delta is one of the major oil-producing areas of the world.

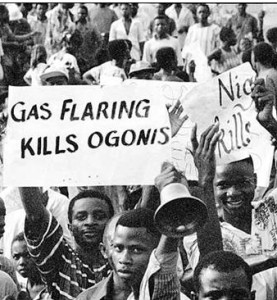

With the oil has come spills: more than 8,000 of them in the last 45 years. Fish populations have been devastated. Gas flaring is causing acid rain throughout the region, ruining agricultural lands. More than 15% of mangrove forests have been destroyed outright. The people have not benefited from the oil extraction. More than 70% of the delta’s residents live in extreme poverty, their traditional livelihoods destroyed by pollution and no revenues forthcoming from the oil.

Starting in 1970, an organized non-violent resistance movement called MOSOP (the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People) began to agitate for environmental justice, democracy, and human rights in the region. For 25 years, the movement spoke out against injustice, organized protests, developed alternative policies, and orchestrated sit-ins in oil facilities.

Then, in 1995, the Nigerian military police (assisted by Shell’s private military forces) arrested 9 leaders in the MOSOP movement. Framed on charges of assassination, these leaders (including Nobel Peace Prize nominee Ken Saro-Wiwa) were executed on November 10th.

With the non-violent movement floundering and the catastrophe accelerating, some individuals in the delta community decided to take matters into their own hands. They formed a new group called MEND: the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta. Using hit-and-run guerrilla tactics, speed boats, and deep connections in the local communities, MEND began to sabotage oil facilities across the region.

At one point in 2008, MEND disabled 10% of Nigeria’s oil export capacity in one attack, and through a series of attacks reduced production by 40%.

At one point in 2008, MEND disabled 10% of Nigeria’s oil export capacity in one attack, and through a series of attacks reduced production by 40%.

Serious biocentric activists around the world must understand the importance of these actions. Environmentalists in countries around the world have worked for decades to slow and halt fossil fuel extraction, and in not one other case has the capacity of a major producer been impacted to even a fraction of that degree.

No one has been as effective as MEND.

For many decades, activists have been using the same tactics: protests, mass mobilizations, court cases, lobbying. And in many cases, these techniques have been successful, leading to meaningful reform and improvements. But overall, our movements (we speak particularly here to the environmental movement, but the same can largely be said for the anti-racist movement and the feminist movement) have been stagnant and unsuccessful.

These two models — revolutionary democracy and the most direct of direct action — may offer chances at greater levels of success than we have seen in the past 40 years. To learn more about the CELDF model, visit www.CELDF.org or watch Thomas Linzey’s video. To learn more about MEND and the strategic sabotage model of ecological resistance, visit the Deep Green Resistance website.

50% of Europe’s renewable energy comes from burning imported wood.

98% of Indonesia’s rainforests will be gone in 10 years.

50% of China’s rivers have disappeared since 1990.

50% of China’s groundwater is too toxic to even touch.

20% of China’s soil is too toxic to grow food.

In 10 years, 4 billion people will be short of water.

In 20 years, Food & Water Wars will be normal.

In 30 years Mass Extinction goes into Runaway Mode.

Trees Vs. Food https://www.reddit.com/r/collapse/comments/3d4ucy/forests_or_food_which_is_it/

Mass Extinction Numbers https://www.reddit.com/r/collapse/comments/311m7d/collapse_data_cheat_sheet/

Renewable Bullshit https://www.reddit.com/r/collapse/comments/39wy9g/why_green_energy_is_a_false_god/

Pingback: The Climate Movement is Failing. Here Are Two Models to Turn The Tide? - Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

Pingback: Celebrate achievements, or be lulled by hope? - Deep Green Resistance Blog